Clash of technology poles and the fault lines in the technopolarized world

The US-China tech war shadows the stability of the third countries

The technology war that American President Donald Trump openly declared with allegedly imposed restrictions against Huawei accelerated the technopolarization of the world between the United States and China. This process has divided countries by making them choose either made-in-China technologies or alternatives produced in the pro-American block. The Biden administration also inherited this trend, spurring the technology race to gain global dominance for China or strengthen the current hegemonic status for the United States. Nevertheless, Washington and Beijing made a tit-a-tat of embargo-style regulations, unlike one-side pressure during the previous administration in the White House.

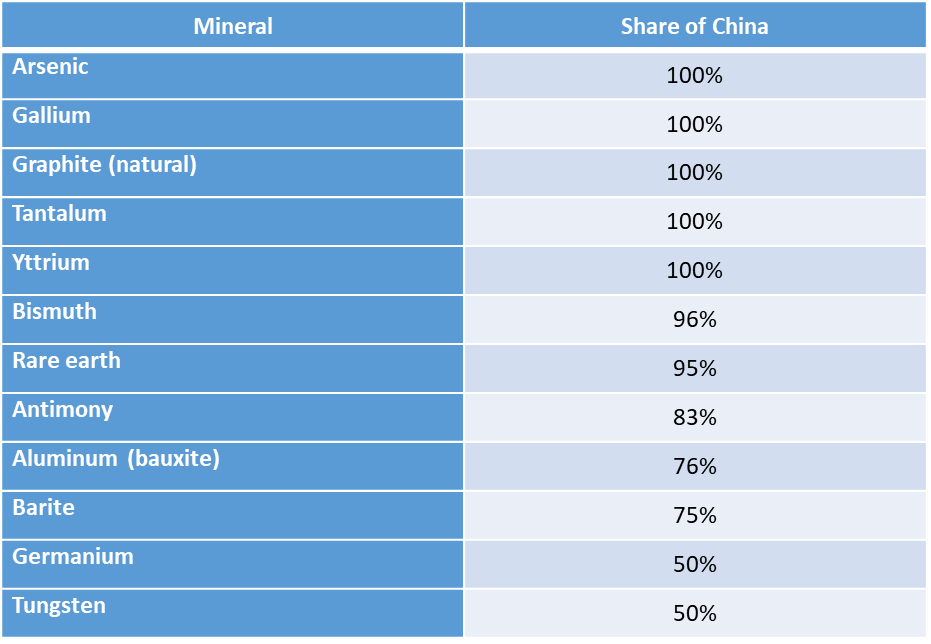

In response to the CHIPS act that bans subsidy-beneficiary companies from operating in China, Beijing began to control the export of critical minerals. When the Asian giant with a global production share of 98.36% gallium, 88.3 magnesium, 80.77 tungsten, and 78.95% silicon announced its intention to retaliate against the restrictions campaign led by the US, Washington, and its allies found how thin the ground their high-tech industry and defense sector stand on. Furthermore, most of the European countries realized that their green energy initiative takes them from the claws of Russian energy and puts them in the hands of China as green technologies require lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements.

Lands without China

To minimize the Chinese effect on their supply chain of technologies, the US and its partners have three options, namely “opening spaces”, “friend-shoring” and “rediscovering continents”.

Reshoring strategy means relocating critical production facilities inside the country from China and states prone to Chinese intervention. Although this choice seems the safest option with new job opportunities in the United States, Europe, Japan, and South Korea, economic and environmental barriers demotivate companies and societies of these countries. First of all, higher minimal wages in the West and allied countries impose burdens on businesses. Secondly, the pollution of the environment due to the production of these minerals may not be accepted by politically active societies.

Friend-shoring approach intends to build capacities in the Western-friendly developing countries where cheap labor for business affairs and stable government for security matters exist. India is the most outstanding candidate in this regard due to its cheap labor, vast market, STEM-skilled graduates, English-speaking intelligentsia, and Indian top managers in top American companies. Moreover, the military power of India to stand against China and its accessible ports to the Indian Ocean endorse the South Asian giant as the next superpower. This is why the West hesitates to move from China to India completely.

When India becomes a technology superpower, it is not guaranteed that Delhi will not compete against the West as China did and is doing. In this case, the years-long strategic relocation turns out to be a change of name of the opponent from China to India. The neutral position of the Indian government about the Ukrainian crisis and the increase of nationalist character in India put the country on the waiting list of potential technology destinations.

The second option of friend-shoring means spreading critical production and mining capacities in Southeast Asia, Israel, and Mexico. Chris Miller and David Talbot offer Mexico as a supreme destination to bring away chip production facilities from China while Arrian Ebrahimi designates Vietnam as a focal point for US chipmakers. Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines could be enlisted since they have cheap labor, previous experience in OSAT, and accessible ports for sea transportation.

However, this option lays the ground for the fault lines in the technopolar world order. As the West struggles to reduce its dependence on the Chinese industry of critical materials and diversify the locations of strategic technologies production facilities, Beijing endeavors to redirect the resources toward its industrial complex and undermine the privileges the US and its allies possess. The race for global hegemony between "technology poles" will be reflected in turbulent political, social, economic, and military tendencies in the fault line countries, possibly including the Southeast Asian region, Israel, and Mexico.

Rediscovering continents to replace the import of critical minerals from China similarly embraces the idea of finding alternative countries and inflames new crisis points in global affairs, but targets Africa and South America and only includes the mining and early-stage processing of minerals. The rich resources of both continents could be directed to the increasingly mineral-hungry technology industries of the United States and China. As a result, both poles may turn the continents into a field of great power competition.

Center for Strategic and International Studies reports that the calculated global share of critical minerals in Africa contains 85% manganese, 80% platinum and chromium, 47% cobalt, 21 graphite, and 6% copper. On the other hand, South America produces around a third of global copper and lithium according to International Energy Agency. These facts mean that the green energy transition, precision arms race, and digitalization increase the geopolitical significance of the regions to line their minerals toward technology production hubs of the world.

The world of many Congos (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Democratic Republic of Congo is an existing example of how the rush for minerals turns a country into a failed state. Although the roots of the Civil War in Congo are connected with the demand for luxury minerals, critical mineral bases of the country may cause this situation to continue with Chinese and American participation. In statistics of 2022, Congo produced 130,000 tons or 68% of the global share of cobalt. Chinese companies already account for 76% of cobalt mining from 61 active mines while 10% share belongs to Swiss commodity trader Glencore.

The struggle between the Chinese and American poles in the technology sector increases the political, social, economic, and military crisis possibilities in Africa, South America, Southeast Asia, Israel, and Mexico. Along with Congo, the fault line countries of the technopolarized world carry several characteristics:

The abundance of critical minerals that are used for green energy technologies, modern warfare equipment, artificial intelligence, and space exploration

STEM-skilled and cheap labor who have previous experience in the semiconductor industry

The countries where the facilities of Taiwan can be relocated in mass

Washington and Beijing speculate the areas that contain one of these three features to get the upper hand on one another in the technology race. The turbulence in the technopolarized world resembles turmoil in the Middle East for oil and gas or the tug-of-war for ideology spaces between the USSR and the US during the Cold War. Although China has taken the role of the Soviet Union, the manners of intervening in the fault line countries remain nearly unchanged. In other words, the countries with abundant critical minerals, cheap and adequately skilled workforces, and semiconductor production facilities find themselves under speculation of the leaders of the two poles.

Peace to the world

Is it possible to avoid crises along the fault lines? The answer is “no” as China and the US are going toward realism from liberal world order in light of the weakening role of international institutions. However, there are several trade-offs that could mitigate the tug-of-war.

Firstly, scientific findings in chemistry and physics may invent alternative types of minerals that China controls a substantial global share in production and mining. It eases the Western quest for new sources of critical minerals in Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America and makes Beijing abandon its tight fist in the industry.

Secondly, the Chinese advancement in the semiconductor sector gives a decisive blow to the opposite pole as the United States mainly utilizes export restrictions in high-tech chips and EUV machines. Domestication of the chip industry in mainland China terminates the sharpest manner of the anti-China block and decreases the need for strategic involvement of China in Southeast Asia, Israel, and Mexico although the clash of poles in resource-rich countries remains actual. The exhibition of the Huawei Mate 60 powered by Kirin 9000s chip demonstrated that China is making progress in domesticating the chip ecosystem.

Thirdly, mature economic conditions, business climate, and the rule of law in the potential fault line countries enable them to avoid political and social turbulences and take advantage of global technology development. Companies from China and the US take part in competition according to the rules a third country has settled in its internal jurisdiction while pursuing their activity in the semiconductor industry and critical minerals mining. In this condition, the government of that third country feels itself on the ice as a corrupt or lobbied decision on behalf of one side may break the whole political and social environment. Except for Israel (over-connected on the US) and some African failed states, almost all other third countries have an opportunity to keep a balance between the technology superpowers.

Conclusion

The technopolarization of the world is seeding potential crises along the fault lines that are abundant in critical minerals and semiconductor facilities. Similar scenarios to the fight for ideology spaces during the Cold War and oil reserves in the Middle East cannot be excluded as the industrial artery in the technology sector of both poles becomes tighter. In a world where China is too big to ignore and the US is too close to escape, the countries in which the interests of techno-powers collide cannot solve the case single-handedly. However, they still may provide stability through a healthy economic system, equal business rights, and the rule of law.